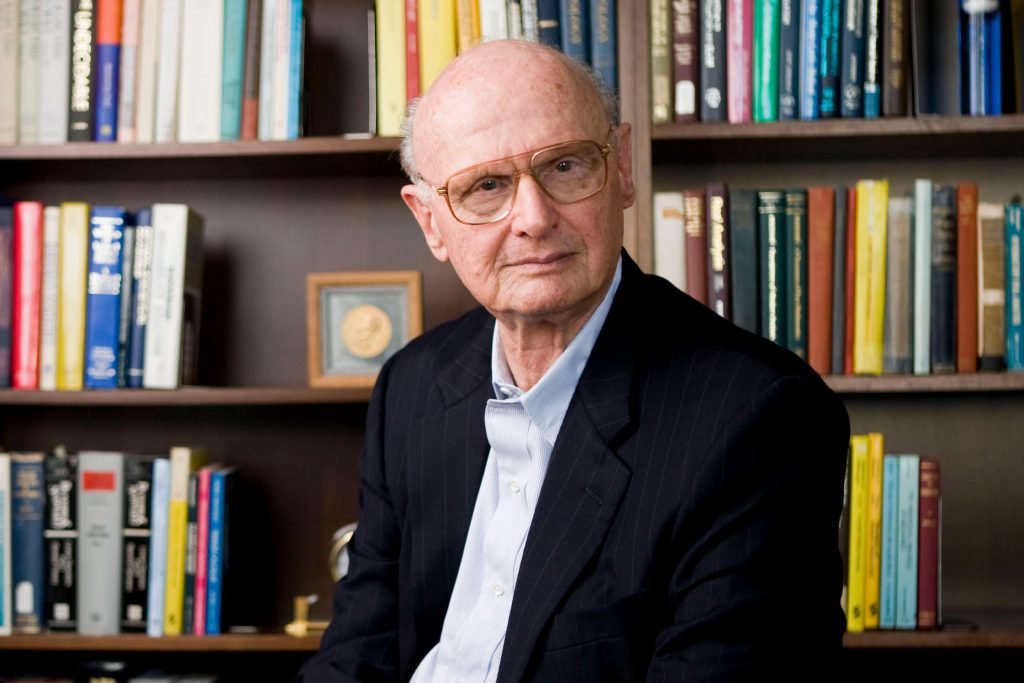

In Memoriam: Harry Markowitz, the Man Who Invented Modern Finance

Harry Markowitz, who died at 95 on June 22, 2023 in San Diego, literally invented modern finance. All of the innovations in portfolio theory since his 1952 PhD dissertation stem from his work. In almost no other field of endeavor has one man been so central to the luxuriant tree – a forest, actually – of ideas that followed.

Harry was not a close friend of mine – we met at some conferences and industry events – but he influenced me profoundly. He was unfailingly friendly and would speak to anyone regardless of their station in life or degree of sophistication. Indicative of his modesty is the fact that he only regarded himself as the co-discoverer of what we now call Markowitz optimization; he credited Andrew D. Roy, an obscure Cambridge don a few years older than himself, with having made the same discovery at the same time. This was formally correct, but Markowitz was an evangelist for his novel idea, and Roy was not. What you do with your idea makes all the difference.

Encountering Markowitz’s ideas

When I entered the investment business in New York in the early 1990s (with some prior investing & data analytics experience), Markowitz optimization was known to every finance academic, and thus to every recent business school graduate. It was considered gospel in those circles.

Yet, outside of a few quant firms and index fund managers, it was not widely implemented by portfolio managers. I was in the minority in embracing what was considered “just an academic concept” by many in the business. Over time, portfolio managers became converted to the use of optimizers to build their active funds. (Most index funds don’t need optimizers – if they are capitalization-weighted, they optimize themselves, so to speak.) While I had always embraced factor investing and indexing, and was using Markowitz’s ideas and mean-variance optimization software to build portfolios, it was a bit of a lonely quest at first. Now it’s almost universal practice.

As you can tell from the way I’m telling this story, Harry Markowitz influenced me a great deal. We even had some personal characteristics in common. He liked comic books and so did I.

The origin story of Markowitz optimization

One day in 1949, a very young Harry Markowitz was in the waiting room of his University of Chicago PhD advisor, Jacob Marschak, hoping to get some guidance on what to study for his PhD dissertation. A stockbroker who was also in the waiting room suggested he study the stock market. At that time, the stock market got almost no academic attention and was considered somewhat disreputable. Having peaked at 381 in September 3, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell a heart-wrenching 89% over the next three years, closing on July 8, 1932 at 41. The market crash was, of course, closely associated with the Great Depression, the worst economic event in U.S. history.

Some younger readers may ask, “41 what?” Forty-one on a scale of today’s Dow being roughly 34,000, that’s what. The Great Depression was a catastrophe on a scale we can now scarcely imagine, and it was also the buying opportunity of the century. But few people could buy at the low point because nobody had any money. That’s why the market was so cheap![1]

By 1949 the Dow had clawed its way back to a range of 161 to 201. Few people were impressed.

This lousy performance since the 1929 peak had made the late 1940s and early 1950s a propitious time to invest, and an even more favorable time to make one’s mark in the academic study of equities. Markowitz had no real competition.

Harry followed up on the stockbroker’s suggestion and, by 1952 at the age of 24, had completed his dissertation, which laid out the mean-variance paradigm that we all now use to balance expected return against expected risk. He did this in the context of individual securities, not asset classes, so the calculations needed to identify the efficient frontier were nightmarish. No computer then in existence was up to the task. As a result, Markowitz’s method was not practical until his protégé, Bill Sharpe, developed the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). The CAPM is a much simpler way of implementing Markowitz’s central insight, which was that investors should maximize the expected return of an entire portfolio, not its individual security components, at each level of expected risk. I’ll return to the CAPM later.

Meanwhile, back at the University of Chicago, Markowitz had to defend his dissertation in front of a tough crowd: the senior faculty members Milton Friedman, Tjalling Koopmans, and Leonard “Jimmie” Savage, as well as Marschak. After Markowitz presented the case for his dissertation, Friedman said, “I’ve read your dissertation and can’t find any mistakes in it. There is just one problem: this is not a dissertation in economics. We cannot award you a Ph.D. in economics for a dissertation that is not economics.”[2]

Moments later, or maybe after a short discussion among the advisors, Friedman said, “Welcome to the faculty, Doctor Markowitz.”

The core idea

Markowitz wrote in English, not mathematical Greek, so let’s go to his own work for a description of the core idea. He begins with some background:

The basic concepts of portfolio theory came to me one afternoon in the library while reading John Burr Williams’s Theory of Investment Value.[3] Williams proposed that the value of a stock should equal the present value of its future dividends.

If investors really followed this formula, and if future dividends could be known with some confidence, they would find what Williams called “the best at the price”: you could rank all the stocks by their present value and there would be one best stock. Markowitz continued,

To maximize the expected value of a portfolio one [would thus need to] invest only in [the] single [best] security. This, I knew, was not the way investors did or should act. Investors diversify because they are concerned with risk as well as return. Variance came to mind as a measure of risk. The fact that portfolio variance depended on security covariances added to the plausibility of the approach.

At a practitioner level, the core idea can be summed up by saying that one should select not securities one-by-one, based on their individual merits as had been the practice since time immemorial, but portfolios. The portfolios should be constructed to minimize overall risk at each level of expected return, or (alternatively) to maximize expected return at each level of risk. The individual security characteristics don’t matter other than as they affect the return and the risk of the portfolio – which depend, in turn, on the correlations or covariances among the individual stock returns. This insight of Markowitz’s was truly revolutionary, because security analysts had focused on specific companies and not how the fortunes of each company might co-vary with the others that one might hold.

I’d love to be able to say that, after 1952, investors never again looked at stocks other than in a portfolio context, but it was not to be. As my personal story reveals, the evolution of portfolio management into a quantitative science based on Markowitz’s ideas would take several decades.

Problems with optimization

There was just one hangup in actually using Markowitz’s math to calculate optimal portfolio weights: the number of covariances one had to calculate was overwhelming. If you’re trying to find optimal weights for an opportunity set of 500 stocks – which is realistic because I run a small-cap fund where you have to analyze a lot of stocks – the number of correlations that need to be estimated is 500 x (500-1) / 2 = 124,750. This is a well-nigh impossible task. Even if you completed the calculations, they would still be rough estimates, not exact numbers. The estimates are rough because the historical data typically used to make the estimates are not necessarily good forecasts of future correlations. The future correlations are, of course, what’s really relevant – and they’re unknowable. The same difficulty with the future-equals-past assumption applies to the expected return and expected risk (standard deviation) of each asset.

In 1964, Sharpe’s CAPM makes the Markowitz insight practical

To radically reduce the number of calculations, Markowitz’s protégé Bill Sharpe assumed that only the part of an asset’s risk that is correlated with the risk of the cap-weighted market is “priced,” that is, rewarded by the expectation of a higher return. (There was a legitimate theory behind the assumption; it was not just an expedient.) The resulting model, the CAPM, is almost trivially easy to estimate. For 500 stocks, instead of 125,250 correlations you only have to estimate 500 betas, plus the expected return on the cap-weighted market in excess of the riskless (Treasury bill) rate. Given this information, the overall portfolio risk and return are easily calculated.

Sharpe’s solution to this problem was shocking in its simplicity and in its implications for asset pricing. If one believed the model, all asset management could be reduced to a few calculations.

The CAPM thus became the standard approach to understanding the risk-return relationship for decades, despite having the same estimation-error problems as the original Markowitz method and despite being an incomplete model of reality.

I’ll skip further details on the CAPM because this post is about Markowitz, not Sharpe – but Sharpe’s recasting of the optimization problem made it practical to use Markowitz’s insights in portfolio management, and is therefore important to Harry’s story. While the CAPM has to some extent been eclipsed by more complete models with multiple factors, Markowitz optimization is still with us in basically its original form. It is a lasting, general-purpose technology.

Conclusion: Toward the democratization of good investing

When Harry Markowitz began writing his dissertation, the investment business had no way to build efficient portfolios, no performance measurement, no performance evaluation and attribution, no index funds to compare an active manager to. Today, we have all that plus a plethora of funds, strategies, and exotic financial instruments with which to match investor preferences to issuers’ need for capital. All of this innovation (not all of it beneficial, but it mostly is) stems ultimately from that 1952 dissertation of which I’ve spoken so reverently.

Today’s capital markets are not perfect. We still have fraud and misrepresentation to cope with. But the wide availability of tools that grew out of Markowitz’s work has made scientifically managed investment products available to everyone, if they are well enough informed to choose those products.

I always appreciated how Harry’s ideas could help any type of investor of any size. Portfolio optimization wasn’t just a theory that applied only to institutional investors or wealthy people. It is a concept and technique that could (and eventually did) wash over Main Street and affect all investors. Harry Markowitz’s legacy is the democratization of rational, scientifically informed investing. We are all better off for his having lived and done the work he did.

[1] This phenomenon is called procyclicality; it’s underappreciated and very important, because it explains why it’s hard to make money in the stock market. When it’s a great time to buy, few people have the means to buy (and are scared by recent past declines), but when it’s a terrible time to buy, many people have the money (and are excited by the size of recent past returns). Thus, in an apparent paradox, the average experience of typical investors in the market is much worse than the performance of the market itself.

[2] Markowitz, Harry. 1959 [1991]. Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments, p. 382, quoted in http://econjwatch.org/file_download/743/MarkowitzIPEL.pdf

[3] Williams, John Burr. 1938. The Theory of Investment Value. Harvard University Press.